By Sara Valle

There’re so many different reasons to enumerate to explain why book banning is wrong, that I don’t even know where to start. Mainly and quite plainly, knowledge is power. The advantage of having access to an education, to the written word, has made us more malleable and curious.

We want to read memoirs like Patti Smith’s Just Kids to evoke 60s and 70s Bohemian New York and know all about her initially romantic partnership with Robert Mapplethorpe and how it evolved to a profound platonic connection that inspired their artistry.

We want to read stories based on real events like The Choice not only to feel the connection through pangs and pains, but also to learn from the monstrosities humankind’s committed and been through. We want to read about what life is like in other worlds – even the fictional ones, like Middle-earth. There’re many other reasons why reading is beneficial and useful – it kindles our eagerness to know and feel more; to learn more.

Reading is a pleasure. We all spend time sitting in the tube playing games about candy exploding and ninja-style fruit slicing, scrolling through endless photos and videos of people that appear to have fancier and better lives, replying to messages in group chats with family members or friends we barely see. But sitting down to pay attention to what’s in front of our eyes is a whole other story.

“I don’t have time to read” has got to be the most used excuse to allow ourselves to close a book forever. The truth is, I think we’ve grown impatient and we want things quick and, if possible, hassle free and yesterday.

The audiobook version is yet to take over the – probably wildly inaccurate – movie version of books, although we all know someone who puts on their headphones and listens to some voice actor or celebrity’s voice going over a romantic novel or a thriller so they can keep on with their chores, exercise, or go for a walk without feeling like “they’re wasting time”. When did reading become so hard and even tedious for some?

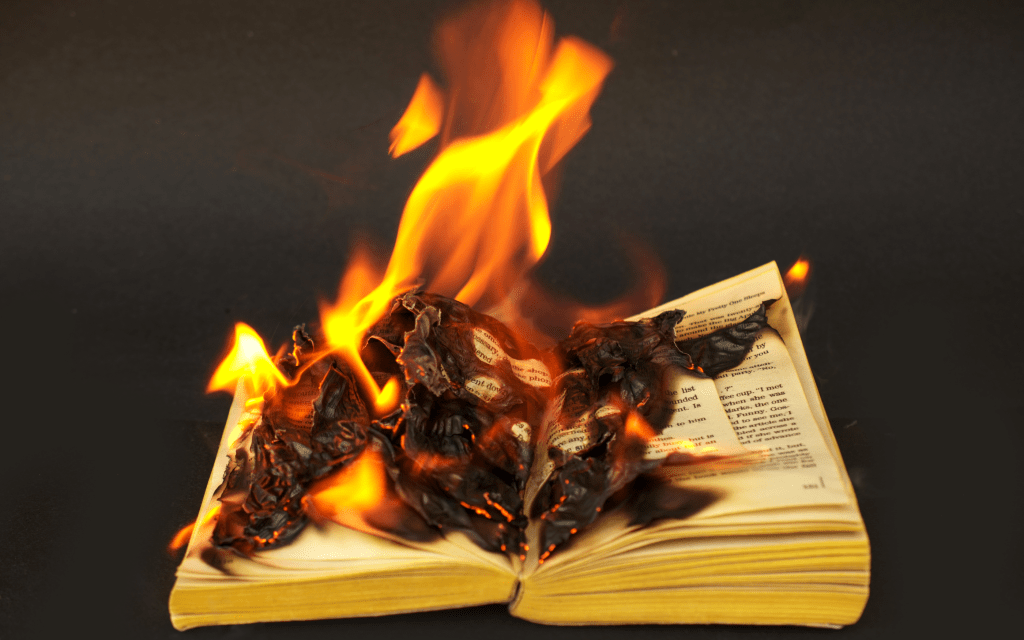

I guess we’ve become used to it and forgotten that reading and having access to books is not only a pleasure, but a right. The earliest records of book banning date back to before the Common Era, more specifically to the Huang Dynasty, when the Chinese emperor Shih Huang Ti burnt all books of the past and buried alive 460 Confucian scholars to erase history. You probably know why wiping off history could be useful for an overbearing and controlling emperor, right?

They say the pen is mightier than the sword. So this yearning for controlling knowledge, and therefore power, has been the main reason certain books were banned in the first place.

The original culprit of book burning in the common era were the Puritans. The first book ban in the United States took place in 1637 when a chap called Thomas Morton published his New English Canaan. The book was considered a harsh and heretical slam on conservative Puritan life, which Morton had first experienced after moving to Massachusetts a few years prior.

Apparently, Morton was an olden-day metrosexual entrepreneur with a keen interest in nature and pagan festivities that was friendly with the Native Americans – what today would be considered “woke” back then was just a “nope”, so he was ostracized and exiled.

Obviously, this wasn’t the only book the Puritans banned, as William Pynchon’s The Meritorious Price of our Redemption, a pamphlet that refuted Puritan doctrine, faced the same fate just thirteen years after, in 1650. Let’s say that anyone who dared to go against the word of God or dress in something other than sadd-coloured high-neck smocks was in the spotlight.

The idea of people having freedom of expression and thought has always been terrifying for the Church and governments since the creation of societies. So brandishing the control over what’s published was key to keep people in their place and the Church got rid of Tyndale’s New Testament in the 1520s (and hang and burnt him); created the definitive list of books that Roman Catholics were told not to read in 1559; and jailed Galileo in 1616 for his theories about the solar system, which forced his widow to destroy some of his manuscripts after his passing. And these are just some examples.

It’d be nice to think this is something kind of ancient, so antediluvian that transparency has become the norm. Unfortunately, it’s not. Hundreds of books get challenged and banned every year worldwide for various reasons. You could think this doesn’t happen in the UK anymore, though research carried out by the Charted Institute of Library and Information Professionals (Cilip) found out that a third of librarians are increasingly asked by members of the public to censor or remove books. The most targeted ones involve empire, race, and LGBTQ+ themes. Go figure!

Most government are not getting that involved in book banning anymore, yet the current political environment is certainly not helping much. If this feels outlandish or even like it belongs to a foreign dictatorship, we could also talk about how the editing and hiding of certain other documents almost helped Members of Parliament get away with stealing and abusing the system in the UK in 2009. They even hired people to cross out information from official papers so that the public wouldn’t know about their wrongdoings.

These tactics to dodge questions and avoid people finding out about their schemes also extend to literature. In 1974, The CIA requested copies of the manuscript and demanded the removal of 339 passages from The CIA and the Cult of Intelligence so their dirty tricks and failures overseas wouldn’t be revealed.

This might be too on the nose, but this strategy was also used against one of the most challenged books from the 2000s: Toni Morrison’s Beloved, which explores the destructive legacy in 19th century America. Long story short, you’re allowed to think for yourself as much as your country’s officials want. If you still don’t believe it, we could also talk about the gagging mechanisms used against journalists worldwide – even in the UK – and the ignorance and impotence the lack of freedom of press causes. But let’s leave that for another day.

Making people into machines was also tried and tested through book banning. Roman poet Ovid was the next to get the axe when he was banished from Rome for his love guide Ars Amatoria. Sex sells now; nevertheless, it was a big no-no before men could use it to show their dominance over women in demeaning commercials. Phew, it’d be nice to think we’re over that too!

You could think that Fifty Shades of Grey brought liberation to women all over the world. It was an explicit and raunchy global best-seller written by a woman – too bad it also presented a toxic relationship as couple goals. Although one good thing this book did was opening the door of acceptance to romantic literature and detailed sex scenes, albeit the insufferable movie saga and the copycat books that made abusive relationships trendy for a hot minute.

E.L. James’ books would have been burnt to crisp and banned a few decades ago. In fact, sex has always been one of the most frowned upon topics in literature. Beloved was also deemed to be “too sexually explicit”. Still, D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover takes the cake as the most infamous piece of erotic romance of all time. Just a little of bush-shaking was enough to ban it in the US under obscenity laws and in the UK under the Obscene Publications Act. The female character, Connie, is quite sexually unaware and passive in the whopping three sex scenes which granted it the blessing of being banned.

Henry Miller’s autobiographic Tropic of Cancer went further and also made it to the top of the list for challenging models of sexual morality. Not the best book to read if you’re a woman. However, the dehumanising and sexist tones were not what got all impious and carnal Miller’s works banned. Although you don’t have to go to extremes – just mentioning anatomic parts and hinting sexual connotations was enough to attempt to erase a book’s existence.

People were not allowed to think about sex beyond their reproductive duties back then. For that reason, The Diary of Anne Frank, Sherman Alexie’s The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian, and Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale have been challenged and removed from public library shelves for being “too vulgar” or having “too many sexual overtones”. Funnily enough, all these books are a critique of society in certain way – be it uncovering an uncomfortable truth or overtly denouncing actions and standards through dystopian scenarios. Orwellian much?

Ars Amatoria was also one of the many books burnt by Savonarola in his bonfires of the vanities in Florence in 1497, where he instigated his followers to destroy anything that could be considered a luxury. No indulgence, just obligations for responsible high-functioning machinery – I mean, society! So, books, works of art, musical instruments, jewellery, and manuscripts were burnt as women crowned with olive branches danced around the fire – no wonder his supporters were known as “weepers” (piagnoni).

Whilst this Dominican friar’s extreme views were all for asceticism and by getting rid of luxury he expected to get rid of vice – such as the exploitation of the poor by the rich and powerful, corruption within the clergy, and the general excesses of Renaissance Italy, this popular preacher also got rid of pleasure. Ironically, another big fire was lit the following year under Savonarola himself, who hung from a cross and burnt with his writings, sermons, essays, and pamphlets. Unfortunately, this wasn’t the commoners revolting against austerity, but current pope, who felt uncomfortable with his denunciation of the laxity and luxury of the Church and its leaders.

I guess the only reason governments took over book banning and burning was the creation of secular states. The first time the government took book banning in consideration was when Goethe’s epistolary novel Sorrows of Young Werther was published in 1774. The final chapter of the book graphically depicts Werther’s suicide, which today would come with a warning – at least if it was a Netflix movie. Sadly, there was no such thing in the Revolutionary Era, and the Lutheran Church as well as various European governments banned the book after a series of mimic suicides followed the publication of the book. The excuse of “protecting people” has been used for explaining book banning for years, but at what cost?

…

Read the whole article by downloading Not Boring Volume 3 on HiFi Pig’s site here: https://www.hifipig.com/not-boring-magazine-by-hifi-pig/

Leave a comment