By Sara Valle

It’s a Friday evening and people crowd in front of Islington Town Hall’s majestic neoclassical building. Clouds gather in the sky and confetti piles on the few steps that lead up to the main entrance. Someone has just gotten hitched – their colourful gowns look brighter than the white blanket that’s the sky as they celebrate and laugh. But what lies ahead in the town hall is far from a joke. Children and knives.

Council representatives, Metropolitan Police, and the concerned Highbury and Islington community meet in committee room 5 upstairs. The traffic noise makes it hard to listen to each other, but they settle in their seats and the hubbub fills the room as they prepare the online connection for those who couldn’t make it.

Knife crime is growing, and children are increasingly becoming the target. In broad daylight, when they are ready to go back home after school, Highbury schoolchildren are being cornered, terrorised, and some even frog-marched to the nearest cash point and forced to withdraw money.

Children feel defenceless; parents feel powerless.

“Aside from the expectation that children should be allowed to walk to and from school without the threat of robbery and violence, to allow it to happen and somehow accept that it’s merely part of modern urban society emboldens the perpetrators and encourages them to take even more extreme measures,” says Chris Armstrong, one of the concerned parents. He thinks some adults are just turning a blind eye on the emergent trend.

Targeting the innocent: Children trapped in a spiral of violence

Youths gathering outside of establishments such as McDonald’s near Highbury and Islington are oftentimes frowned upon. During the meeting in the big and cold committee room 5, an angry middle-aged couple complain about how they’re using Lime bikes and “tossing them around”, “using them to snatch phones”, and plainly “being disrespectful towards the elderly”.

These children are not only the victims of their peers but of prejudice. Parents argue this is affecting their academic and social lives, as they no longer feel safe hanging in the vicinity of what they once considered “a village within a city”.

“There should be zero tolerance when it comes to crimes against children, even if it’s children carrying out some of the crimes against their peers.”

“There should be zero tolerance when it comes to crimes against children, even if it’s children carrying out some of the crimes against their peers,” states Chris, who passionately and fiercely wants to protect his teens from what seems to be a sooner-or-later one-path fate for children in London.

Chris is one of the many parents whose children attend the couple schools near Highbury and Islington that are being targeted by what Metropolitan Police believe to be organised gangs.

Parents patrol to fight back against crime

Most of the times the muggers use nothing but words to intimidate their victims, but in January 23 this year, a St Mary Magdalene Academy pupil was injured after a knife was pulled on him by young thieves in balaclavas.

Since then, parents have started organising patrols in hi-vis vests just “to show their presence” in hopes they can prevent other incidents from happening.

“The idea is we’re not going up to kids or we’re not talking to anyone. We’re just being there and we’re just being an adult presence,” says Amanda Lang, the head and brains of the rota for parent patrols. But she fears this is not enough.

“We were just so sick of our children being attacked and in such danger,” she says. “I hope you can hear I’m just trying to stay really calm,” she sighs down the phone. She’d like to keep her privacy for her children’s sake despite being at the heart of the operation. “My phone just buzzes a couple of times a day and I look at it with one eye like, ‘oh my God, I hope this isn’t awful news’.”

In the hour-long conversation, Amanda talks about how these constant messages are what made her decide to take the vigilante strategy. Since they started, she’s seen teenagers on bikes and scooters with no school uniform go around the streets, hand-signalling codes, and phone-calling others to join their ambushes. They know they can’t be chased without crash helmets.

“I’ve seen an older teenager holding the fingers of a younger kid, and when he didn’t have enough to give him that day of stolen property, he looked like he was going to break his fingers.”

Her concern, as well as other parents’, is that this is bigger than they can even fathom. They can’t see an end to the situation despite being hopeful police intervention can improve it.

“These are young teenagers and we’re seeming to find there’s always someone above them making them do this,” says Amanda, distressed but stoic. “I’ve also seen it’s the older ones who have organised this. I’ve seen them catching up with the younger teenagers, saying: ‘What did you get for me today? Show me your bags’. And when these kids didn’t have enough for them, enough stolen phones and stolen clothes, they were violent towards them.”

“I’ve seen an older teenager holding the fingers of a younger kid, and when he didn’t have enough to give him that day of stolen property, he looked like he was going to break his fingers. It was so scary,” she recalls in a voice choked with what seems to be fear.

Islington’s knife crime crisis

Islington is the third most dangerous borough in London, according to CrimeRate.co.uk, a data analysis and GIS project dedicated to uncovering crime trends in England, Wales, and Northern Ireland.

The overall crime rate in 2022 was 22% higher in Islington than London’s general rates, with 116 crimes per 1,000 people compared to 95 per 1,000 residents London-wide. Despite this, the events just recently put Highbury and Islington on what Metropolitan Police call a “hot spot”, after more than six incidents of the same nature were reported within two weeks.

“We kept getting parents contacting us because they were worried, so we’ve reported it to the police; we’ve reported it to the Council, and they’ve increased patrols,” says Highbury Councillor Caroline Russell. She’s packing up as she speaks, probably wishing she’s not last to leave the room.

“It has reduced the number of crimes and made a difference,” she adds before redirecting the conversation at the commanding presence that is Police Constable Johar Akhmiev.

He’s taken over PS Iain Reid for the day, but he’s brought his slides with him to prove that the 5-year trend shows there’s been a 5% reduction in crime in Islington and Highbury as a whole. Still, Angel and surrounding green areas are robbery hot spots too.

Standing in his sleek black vest, arms behind his back, he tells the group there’ve been nine arrests over the last three months and they’ve found knives and other weapons – including a machete – hidden in bushes. The emblazoned police logo is supposed to project authority, but the numbers are discouraging and muggers are not scared.

The Flying Squad and the Violent Crimes Taskforce have intervened to stabilise and reduce violence too. Some are content with these measures, but others believe not enough is being done. At least, not soon enough.

“We don’t have the resources to have as many police officers on the street as before. We do have minibuses and we always drive around in one ourselves,” admits PC Akhmiev to the hesitant community. These buses are supposed to be a visual clue for muggers to understand police are nearby and offset crime.

Not enough to crush violence

The small yellow hands on the online meeting screen keep popping up as more have questions that need urgent answers. For these parents, waiting for something to happen six times before measures are put in place seems like a long wait.

“If we actually analyse that, what is being said is that it’s okay for six schoolchildren to be mugged at knifepoint before the authorities feel the need to throw resources at it, which in many parents’ view is totally unacceptable,” says Chris. This would make anyone in the meeting room stir in their upholstered green chairs, but he’s not present, as he’s getting ready for a business trip.

“The place is swarming with police when a football match at Arsenal is on and there’s rarely trouble. However, controlling crowds seems to take a priority over protecting school children, which seems totally wrong.

“Another solution is to throw some much-needed resources to try and tackle why this is happening,” adds Chris. “We need to look at why those kids feel that their only option is to go out and mug other kids. This is sadly an area that has been neglected and cut back on during the very damaging years of austerity that followed the financial crash in 2008.”

Chris is thankful that the council, especially Councillor John Woolf, are involved in the issue. But he thinks resources are limited by government-set budgets and the issue is not being tackled. “If it’s happening at all, then not enough is being done.”

When reaching out to Mr Woolf, he happily agreed to chat but he’s been out of office since and the email sits in his inbox awaiting for a reply.

Children caught in the knife’s edge

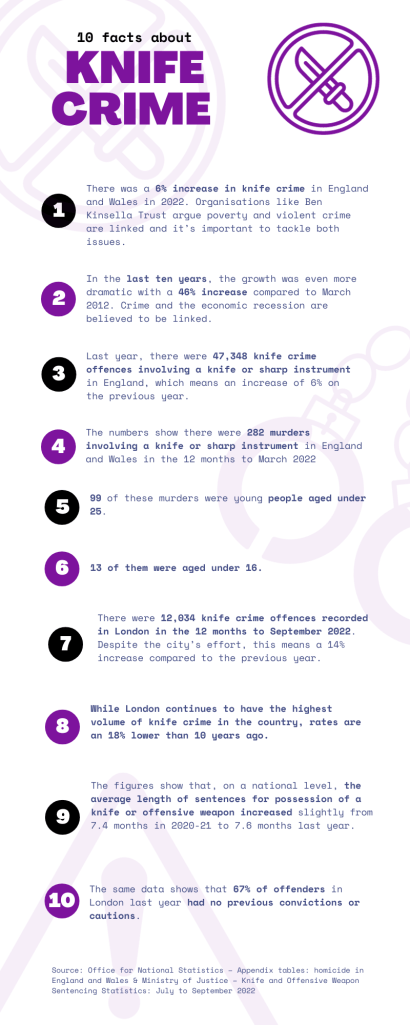

Knife crime is rife in what some call Lawless London. The Office for National Statistics reported that the number of people killed with a knife in England and Wales in 2021/22 was the highest on record for 76 years with a particular rise in the number of male victims.

The largest volume increase was for teenage boys aged 16 to 17. Patrick Green, CEO of anti-knife crime charity the Ben Kinsella Trust – which was set up in 2008 following the fatal stabbing of 16-year-old Ben Kinsella in north London, mentioned the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic as a reason for knife crime rising faster amongst teenagers than any other group.

Green said gangs are skilled at picking up on vulnerabilities to lure young people and exploit them in criminal acts. He also highlighted data from the ONS report that shows knives or sharp objects were used in 75% of teenage murders with just 40% in adults.

In April, a teenage boy was rushed to hospital after he was stabbed in the head outside Arsenal tube station. Parents of the St Mary Magdalene Academy are concerned the incidents could be linked. They’ve recently got in touch with JIGSAW Get Connected, a community interest company dedicated to “improving the lives of young people and their families through early intervention and solution-focused approaches”. Organisations like them are offering support by targeting the issue at the root.

This attention is particularly important in teenagers, who are oftentimes the most vulnerable.

Rachel Vora, an accredited child psychotherapist and founder of CYP Wellbeing, believes children should be given more attention, as adolescence is a key time in everyone’s life.

“The prefrontal cortex is still developing during the teenage years, which can lead some children to make impulsive decisions, engage in risk-taking behaviours and express strong and/or extreme emotions. Teenagers are not yet able to process the potential consequences of their actions, so they are vulnerable to making poor choices,” Vora says.

“During adolescence, there is an increased focus on needing to belong and ‘fit in’ with your peers. Adolescents can often fear being excluded or isolated from a peer group if they do not follow the actions of the group, so ‘peer pressure’ can be a reason for participation,” she adds.

Vora believes that’s the main reason this gangs can successfully operate. Parents have the difficult task of being role models and saviours, but this becomes increasingly difficult when they can’t rely on schools and the authorities to protect children.

Schools are no longer safe haven for children in London

“Schools are supposed to be the definition of a safe environment for children, for learning and for mental growth,” says Barbara Rangel, a teacher working in an inner London school.

But these children can no longer rely on that stability. Walking back home after school has become an ordeal. They don’t know if they’ll be able to keep their belongings nor their self-esteem safe after 4pm.

“Witnessing a mugging right outside of school will make this safe place turn unsafe. I imagine that many students would experience anxiety over going to school, which for those who already experience mental health issues could be incredibly detrimental, as they are more inclined to become school refusers.”

These muggings are not only a risk to teenagers’ well-being and academic attainment, but for also for their development as they become adults in a major city that is suffering a youth knife crime epidemic.

“It just seems symptomatic of society today that it’s expected that school children will be mugged at knifepoint if they live in an urban area,” says Chris, apparently distraught. “The fact that this is even tolerable amongst our politicians and the authorities whose job is to protect them, demonstrates just how low we have sunk as a collective society if we’re not too bothered about protecting our kids. Apathy seems to reign in today’s dismal society.”

When the meeting ends, confetti’s still on the stone steps. Nothing has changed yet.

Leave a comment